As the parable of the “Streetlight Effect” is often told...

Late one night, an officer on patrol spots a man searching for something on the ground under a streetlamp. “What are you looking for?” the officer asks.

“My house keys,” the man replies in frustration.

The officer kneels down, and after several minutes of helping the man look for his keys he asks, skeptically, “Are you sure you lost them right here?”

“Actually, no,” the man admits, and points down the darkened path, “I lost them walking through the park over there.”

Bewildered, the officer asks, “Then why are we looking for them over here?!”

The man now points to the illuminated circle beneath the streetlamp and says, “Because this is where the light is.”

Like the man searching for his keys under the streetlamp, teachers and school leaders find themselves drawn to the picked-over ground of Big Data in education not because it’s where the answers are but “because it’s where the light is.” Big Data-driven decision making can insulate and isolate conscientious school leaders if it’s not illuminating the problems they have and the solutions they need. It can prevent responsiveness to issues with less robust data collection while crowding out alternative qualitative data sources, and demand additional attention and resources where none may be warranted. Over time, the values, mission, and life of a school can be subverted to serve the needs of the streetlamp over students, “because this is where the light is.”

What’s worse, the visible light humans use to navigate the world represents far less than even 0.1% of the entire electromagnetic spectrum, meaning what we see is just a small snapshot of what actually is. Snakes can sense their prey through infrared radiation. Migratory birds are guided by the earth’s magnetic waves. And bees view flower gardens in ultraviolet light. As humans, our superpower is developing, iterating on, and employing clever tools and technologies to help us make sense of and interact with the world as it is with more than just the visible light our eyes can see. A flashlight, for example, repurposes the same technology of the streetlamp to point in whichever direction we choose. Given a tool to see the nighttime differently, the same man in our parable would be able to venture confidently from under the streetlamp and find his keys with ease.

Schools have access to more student data than ever before, yet the data they have is often untimely, confusing, and doesn’t translate into sustainable systemic change. As districts have begun to grasp the scope and scale of the serious structural issues their students face today, conscientious school leaders are telling us they want to move beyond the same stale quantitative data toward actionable qualitative insights at scale.

Polaris Education is a new empathy interview tool in development by Human Restoration Project.

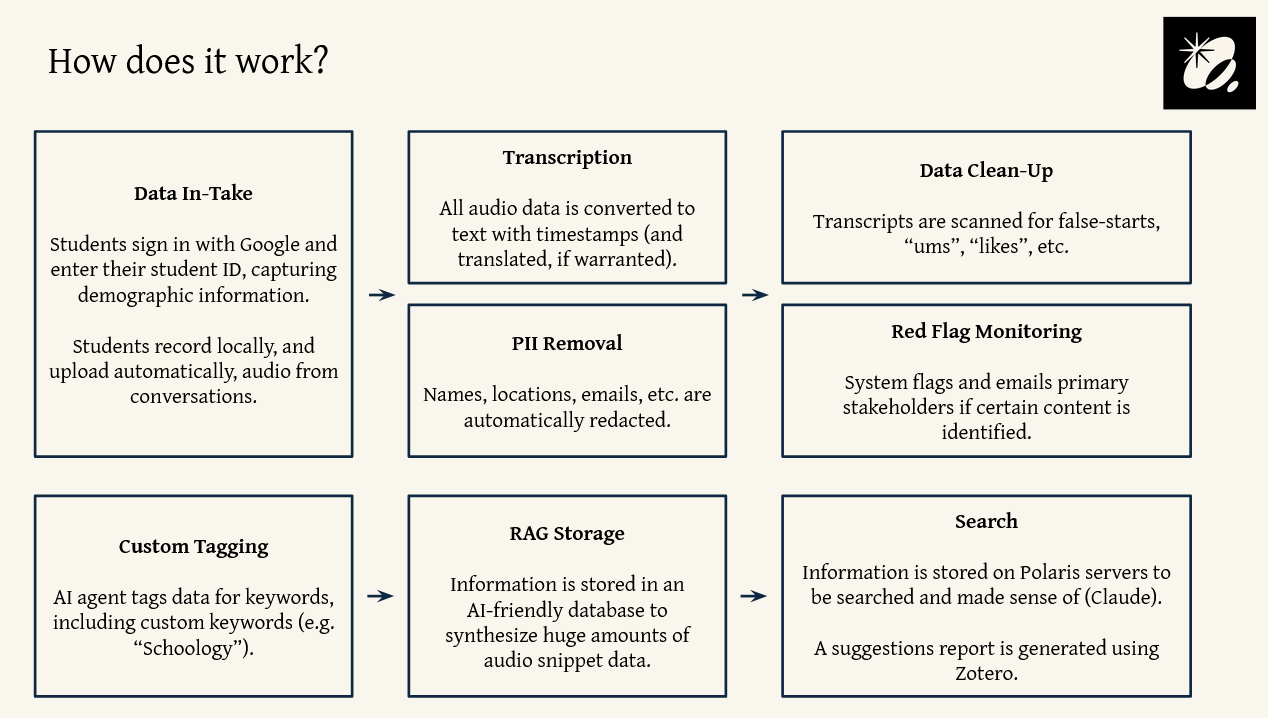

Polaris makes it possible to conduct and store empathy interview conversations, make sense of qualitative data at scale with human-assisted AI tools, and ensure school-based change is informed by student voices.

"Educational change, above all, is a people-related phenomenon for each and every individual. Students, even little ones, are people too. Unless they have some meaningful (to them) role in the enterprise, most educational change, indeed most education, will fail. I ask the reader not to think of students as running the school, but to entertain the following question:

What would happen if we treated the student as someone whose opinion mattered in the introduction and implementation of reform in schools?" —Michael Fullan, The New Meaning of Educational Change

Enter Thick Data.

"Thick, or small data, is human-scale data, collected from small samples in everyday contexts, making visible the motivations, values, preferences, perceptions, and environments of people often left out of public consultations or large-scale datasets…Data that can explore behaviours and intentions, within the places and spaces people live their lives, is data that can help to inform how to frame public policy problems, and how to identify leverage points and attractive interventions – all from the perspective of people on the ground." —InWithForward, Thick Data Primer

Thick Data, in contrast to Big Data, gives us the permission to put all of our sensemaking tools at our disposal, not just what we have the most of, to understand the complicated human endeavor of teaching, learning, and schooling. While Big Data arrives in large standardized quantities and without context, Thick Data is informed by context, stories, and values that can help us make sense of individual experiences.

As one analysis of case studies in applying Thick Data to public services cautions, “The ongoing focus on big data may compel [managers] to feel that they need to ‘do something’ with the data, whether or not this is necessary or useful.” The authors remind leaders and policymakers that, “Big data is a means to an end, rather than an end…[while] Thick data can identify unexpected problems or previously unexpressed needs.” (*) And if the scale of Big Data leads us to make predictions about what might be contributing to outcomes and make tweaks over the summer that may show up in next year’s data, Thick Data lets us go directly to the source to ask “why?” and make evidence-informed changes that impact who you are currently serving.

Another case study from The Handbook of Positive Psychology (2008) provides an exemplar in the power of moving from big to thick data. In the early-2000s, the state of California commissioned the Healthy Kids Survey, taken by over 2.5 million students from 2003-2006. As you can see, while the massive survey data highlighted some alarming state-level trends, it’s far less clear how districts and school leaders could move from the quantification of “meaningful participation” among California 9th graders, for example, toward local actionable change for the 9th graders in their buildings.

The two researchers tasked with making this work “realized that ultimately, the only effective approach to improving schools’ and communities’ provision of these protective factors was to ask the youth themselves how they knew if an adult at school or in their community cared about them and believed in them, as well as what opportunities they had for meaningful participation..." As a result, they embarked on a listening tour, conducting 25 focus groups over 3 years, and from those focus group conversations developed practices for teachers from student feedback. For example, to build caring relationships, students advised teachers to “get to know our stories” and “know our names.” Students also reported that teacher encouragement and reinforcing their belief in students and their future success were key to setting and keeping high expectations.

The impact of this focus group process was not just felt by students, who reported it “Shows us that adults do care about us,” but for adults as well, one of whom commented, “I had forgotten how smart our students really are—and that something all they need is to have us listen.” The act of listening and being heard, being seen as human by other people, was not something captured in the big survey data, and it was made actionable only by unpacking these issues in face-to-face conversation. Ultimately, it just makes sense: If you only have decontextualized aggregate data you can only take decontextualized aggregate action—action that may not actually serve the people you’re intending to help—but solutions are never decontextualized and in the aggregate, they are always local and contextual. And by thinking of Thick Data as “Street Data,” Shane Safir and Jamila Dugan reframe fraught conversations about data historically used to shame and penalize underfunded schools serving marginalized communities:

"It’s time to repurpose data from a tool for accountability and oppression to a tool for learning and transformation. Let’s imagine a new kind of dashboard that lights up with green opportunity zones—classrooms and schools where students of color, LGBTQIA students, and students with diverse abilities experience identity, belonging, and deep learning…Street data will help us pivot from blind compliance with external mandates to cultivating local, human-centered, critical judgment." — Excerpted from Shane Safir & Jamila Dugan, Street Data: A Next-Generation Model for Equity, Pedagogy, and School Transformation

What Polaris offers is an amplification of this important process. Instead of hosting 25 focus groups over three years with a handful of students from a single school and waiting months or years for transcription, analysis, and action, Polaris allows districts to host hundreds of focus groups across a school district in a single week with the potential for every single student to have their voice counted and with nearly instantaneous access to this large body of thick data to immediately inform local decision-making. This level of qualitative “street data” and analysis has never been available to districts and actionable for school leaders. Further, Polaris addresses resource deficits by democratizing access to sophisticated qualitative data tools and processes that were previously only available to state agencies or well-funded districts with extensive research capabilities.

For school leaders using Polaris, their data ecosystem is now a real-time qualitative feedback loop of dialogue and action between students and the system.

By turning Big Data into Thick Data, Polaris transforms abstract quantitative ratings into actionable qualitative insights backed by real student voices.

Step 1: Create a Day of Listening

Create and schedule a meaningful “Days of Listening” with intentional, accessible questions about school climate, programming, or pedagogy that encourage authentic student responses.

Step 2: Multi-Modal Engagement

Students (and adults) participate through voice recordings, group discussions, or written responses during 30-to-60-minute sessions, allowing them to skip questions or explore topics that matter most to them. Conversations can happen in any format students prefer and are conducted in their native languages.

Step 3: We Analyze Your Data

Using a human-first AI process, we remove personally identifiable information, convert data into meaningful categories, and identify key findings linked to current educational research. We prepare comprehensive reports based on student comments directly connected to real audio data, ensuring transparency and authentic voice preservation without algorithmic bias. This work can be expanded upon with students co-leading and presenting analysis in partnership with Cortico.

Step 4: Query Your Data

Ask your data questions like ‘What did sixth graders say about our math curriculum?’ and receive immediate, evidence-based responses backed by real student voices and comprehensive suggestions. (And then as you find more questions to ask, iterate and go back to Step One!)

This project is strengthened by strategic partnerships. Cortico serves as our existing empathy interview technology and infrastructure partner, specializing in amplifying underheard voices through thoughtful conversation powered by human listening and AI tools. HRP has conducted hundreds of empathy interviews with young people on their platform using qualitative research tools. We seek to continue implementaton of Cortico's tools into Polaris Education as a way for students to analyze their own data and lead change at their schools.

Human Restoration Project brings deep expertise to the Polaris Education initiative, having conducted empathy interviews with thousands of young people, families, and education staff across K-12 settings throughout the United States and abroad. To date, HRP has worked with over fifty districts in implementing empathy interviews as a process toward systemic change. Our track record of translating student voice into actionable insights has secured multiple grants and successes, including a five-year Education Innovation and Research grant from the US Department of Education. Since 2020, we have developed a close partnership with Cortico, a collaborator of MIT’s Center for Constructive Communication, to leverage innovative technology in amplifying student voice toward systemic change. Building on this foundation, and our expertise in ethical applications for AI in education, we have developed an alpha prototype of Polaris Education.

We are actively pursuing grants to target the effectiveness of this tool, with RAND Corporation serves as our evaluation partner. They will bring their expertise as a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization that provides leaders with information needed for evidence-based decisions. RAND currently evaluates our Education Innovation and Research grant in Western Michigan through a randomized control trial assessing the impact of project-based learning and portfolio-based assessment on student engagement, well-being, and motivation.

We're partnering with over 100 districts across the United States and abroad to pilot this tool. As districts see the scope and scale of the issues students face today, conscientious school leaders seek to move beyond stale quantitative data toward actionable qualitative insights at scale, and in our conversations they have instantly identified ways they could use Polaris to determine program effectiveness, evaluate new pedagogical techniques, and inform school policy changes.

Polaris Education is in closed beta testing, ensuring our tool best fits the needs of young people and educators. We're looking for additional schools to try out Polaris and are actively seeking grant funding for further research and development.

Join our waitlist and visit the Polaris Education website to learn more. And for more information and how we're seeking to research the impacts of this tool, see our guiding document.